(Photo by: Hassan Ibrahim)

By Nader Bakkar

From an intellectual point of view, the Salafi movement is a rich one, distinguished by varying interpretations within the same school of thought and containing both positives and negatives simultaneously. A group of scholars and independent preachers that belong to this movement have preferred to withdraw completely from the political scene and are backed by scattered groups of Salafis whose votes will not be cast for either candidate.

It is true that this movement specifically, despite its great potential, has been vulnerable over the past three years to significant political and social fluctuations and changes that would overwhelm the endurance of any political ideology or faction. It also must be kept in mind that throughout this era, within the group’s political work, the entire movement has suffered frustration and confusion.

Al-Nour Party is a prominent name within the Salafi movement and represents the movement’s largest contingency. It is the only organised entity within the spectrum of Salafism—the institution of the Salafist Da’wa—and I argue that it is one of the few parties in Egypt that has exhibited a learning curve politically and socially over the past three years.

Since the commotion of 3 July, the philosophy of Al-Nour Party has so far been an attempt at loss management for the Islamist movement on the one hand and prevention of a civil war on the other. After analysing many contemporary experiences, the party expected that the Muslim Brotherhood would not cease clashing with the state, no matter the losses, as a large segment of Egyptian society stood behind them. This issue is what precipitated a clash with the philosophy of Al-Nour Party.

The Salafis had four options during presidential elections, none of which were free from significant political costs that would impact not only the political future of the Salafis but also perhaps their societal acceptance in the long-term. We also must bear in mind that any option that ignores the contemporary context of Egypt, the nature of international variables, or the influence of the last year in which Mohamed Morsi ruled would prove an unrealistic option.

Thus the options consisted of boycotting elections, supporting one of the candidates, namely, Al-Sisi or Sabahy, or leaving the party’s constituency free to choose one of the three above options.

The boycott option was the worst of the four because of its lack of practical impact on the balance of power, along the political cost associated with exercising this option and the other parties’ stigmatising it with negativity.

As for letting the constituency choose freely, this would mean a tacit acknowledgement of incompetence or fear of making a political decision and taking responsibility in front of the masses. The option detracts from the influence of those who exercise it among the parties (currently consisting only of the leftist Egyptian Social Democratic Party, which is one of the oldest parties exercising this option in Egypt).

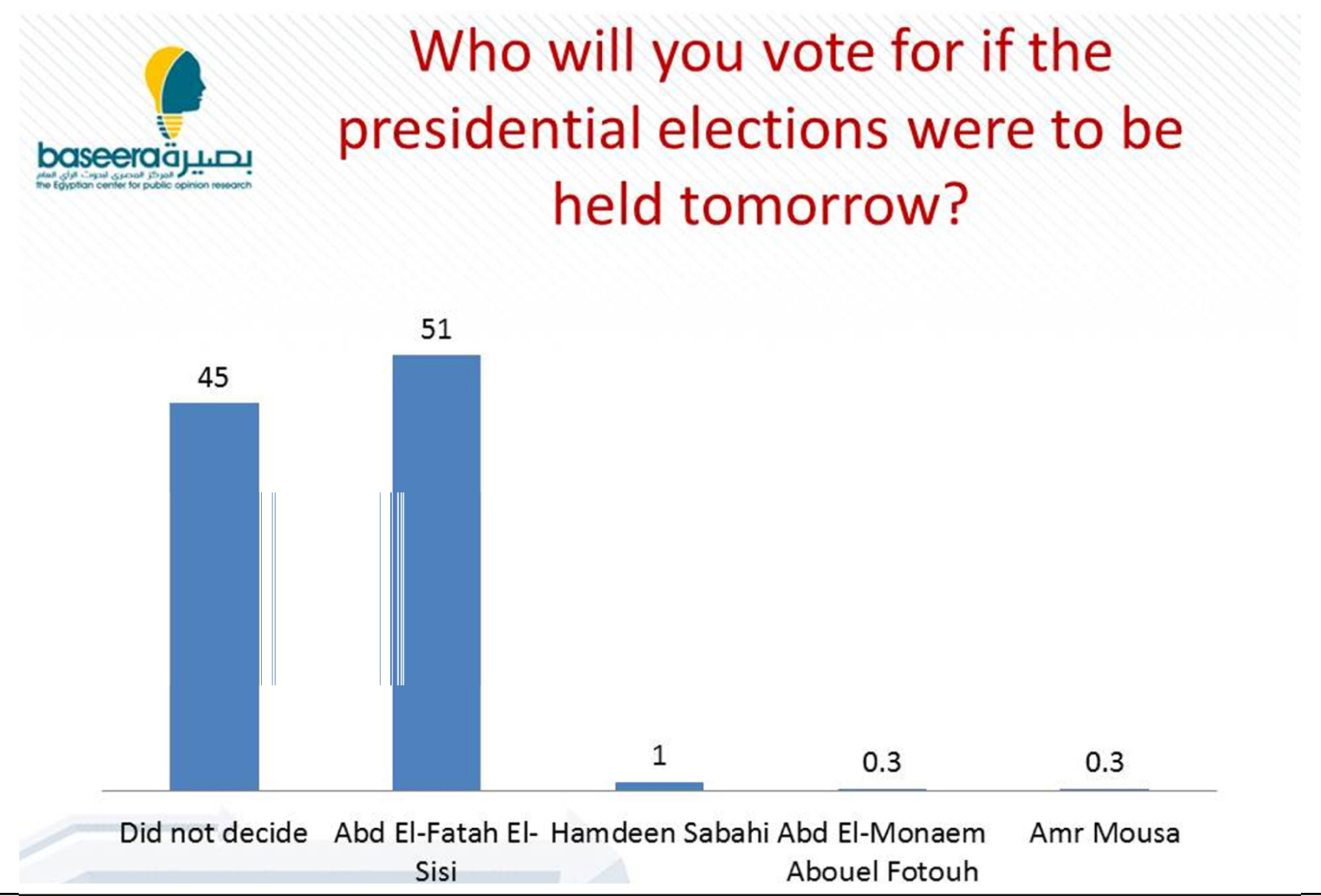

Therefore it was necessary to support Sabahy or Al-Sisi, and this was voted on democratically by the largest decision-making bodies within the party. The result was a large percentage of support for Al-Sisi over his opponent.

Voters within the Supreme Council of the party were reluctant to choose Sabahy because of several prominent points pertaining to the party ideology and Sabahy’s political and economic ideology, in addition to a fear of left-wing dominance over all thrusts of governance much like the Brotherhood attempted to achieve. Yes, the party chose a man like Abdel Moneim Abul Fotouh who did not belong to quite the same school of thought as the Salafis, but at the same time, was not hostile to their orientations. He represented a compromise between liberals, leftists, and Islamists, through which the severity of political polarisation and ideological conflict could be alleviated. This characteristic represents what Sabahy sorely lacks.

As I mentioned, Morsi’s failed leadership experience was fresh in the minds of those who were opposed to choosing Sabahy. They feared a repeat of the same scenario: reluctance of state institutions to work under the leadership of a man whose history lacks any leadership experience and whose record is comprised only of personal struggles. They feared a repeat of the same clash, this time between the leftists and state institutions at a time when the country does not have the capacity to cope with a new conflict.

The choice of a large sector of Egypt’s Salafis, as represented by Al-Nour Party, for Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi was largely consistent with its stance from 3 July until now. The leaders of the party have adopted the philosophy of ‘the most appropriate’ instead of ‘the best’ when comparing candidates.

Originally published in Al-Shorouk Newspaper

Nadar Bakkar is the co-founder, assistant chairman and spokesman of Al-Nour Party. He represented the Salafi movement in numerous conferences and writes regularly for Al-Ahram and Al-Shorouk newspapers.